IMAGE: Queen Cox, Greensleeves, and Fiesta apples growing on the same tree, available from Blackmoor.

I recently discovered the apple “family tree,” which combines up to three different varieties by grafting them onto semi-dwarf stock. The mature tree is about three metres tall, with two or three branches of each variety. They look pretty amazing, with red, yellow, and green apples hanging on the same tree in autumn, or just two early-harvest branches covered in leaves in April, while the rest of the tree remains a wintry skeleton.

IMAGE: Lord Lambourne, Braeburn, and Bountiful apples growing on the same tree, available from Suttons.

Commercially available combinations include Discovery/James Grieve/Sunset, Queen Cox/Greensleeves/Fiesta, and Lord Lambourne/Braeburn/Bountiful. The logic behind these mixtures is fascinating. One strategy is to choose varieties that will cross-pollinate, so that the tree is self-fertile. Apples are self-incompatible, which means that a family tree made of varieties that blossom at the same time will bear much more fruit than a single variety tree with no neighbours.

On the other hand, some prefer to use a family tree to extend their apple season, deliberately combining early-, middle-, and late-harvesting varietals. Another popular strategy is to combine dessert and cooking apples on the same tree.

In short, anyone who can fit a large pot on their patio can enjoy the variety of a small orchard, as long as they prune carefully:

One of the varieties can become the dominant partner, at the expense of the other two. (A bit like life really!) Just keep an eye on this situation, and adjust your pruning to ensure a well balanced Family Apple Tree.

IMAGE: Devonshire Quarrenden (a Tudor favourite), Claygate Pearmain, and Tom Putt (a cider variety developed by a West Country vicar) apples grafted onto a family tree by Nigel Deacon.

I’m a bit of a sucker for apple varietal descriptions, which makes assembling my dream Family Tree a tough but endlessly enjoyable imaginative exercise. The newly digitised British National Fruit Collection makes choosing just three even harder. Perhaps Beauty of Bath (speckled and sweet-tart), Lawyer of Nutmeg (peppery spice flavour), and the Pitmaston Pine Apple (sweet, crisp yellow flesh with a nutty flavour and a pineapple scent)? But what about the Worcester Pearmain (intense colour, strawberry scent) and Ellison’s Orange (soft juicy flesh, tastes like Pernod)?

IMAGE: The Pitmaston Pine Apple, courtesy of the National Fruit Collection.

Of course, all these trees could simply be grown separately and combined on the plate, but there’s something much more exciting about seeing them hanging from the same tree. Restaurants with outdoor seating could engineer pick-your-own apple flights, combining three varieties from the same tree to accentuate nuances of flavour, scent, and texture. Flavour archaeologists might design trees that combine two parents with their better known offspring, such as the Golden Delicious and its proud but obscure parents, the Grimes Golden and Golden Reinette.

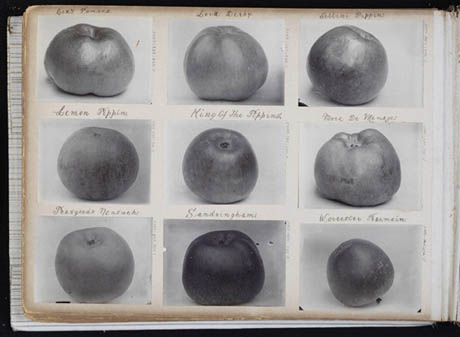

IMAGE: “Page of photographs of apples from an album,” Charles Jones, c. 1901-1920, from the Victoria & Albert Museum’s gorgeous 2007 “A is for Apple” exhibition.

Meanwhile, amateur historians could restrict themselves to nineteenth-century varieties, immersing themselves in an authentic applescape. Anniversary trees would combine varieties brought to market in the same year, such as the Galloway Pippin and Gascoyne’s Scarlet (1871, a year that also saw the first photos of Yellowstone National Park, and the opening of the Royal Albert Hall, among a few other things). Forget trendy cocktail programmes – apple grafting is more nutritious, environmentally friendly, and fun.