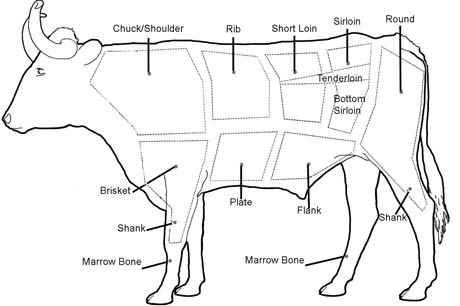

IMAGE: The American beef, via.

In her study of beef and its role in American culture, Raising Steaks, historian Betty Fussell describes the impact of the train on New York City’s meat-processing infrastructure:

As the railroads massively increased cattle traffic to Manhattan, the Pennsylvania Railroad built holding pens in New Jersey, whence barges would ferry cattle across the Hudson to slaughterhouses along Twelfth Avenue and Thirty-fourth Street. Traffic was so heavy in the 1870s that a “Cow Tunnel” was built beneath Twelfth Avenue to serve as an underground passage, and it’s rumored to be there still, awaiting designation as a landmark site.

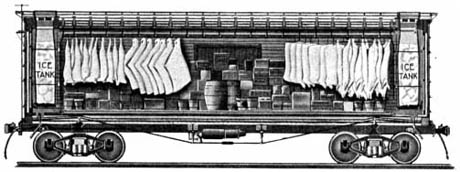

Fussell goes on to note that, soon afterward, the invention of refrigerated train cars (the first effective design, developed by engineer Andrew Chase for Chicago meatpacker Gustavus Swift, entered service in 1880) rapidly made the city’s extensive livestock handling and slaughtering facilities—including, presumably, the Cow Tunnel—redundant.

IMAGE: Early (circa 1870) design for a refrigerated railway car, via.

I love this anecdote. For starters, it shows clearly how food designs the city, carving out routes and reshaping urban infrastructure in response to changes in technology, economics, and volume. Before the railways, for example, Fussell tells us that “cattle raised in upstate New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Massachusetts were shipped by boat or ferry to central stockyards on the Lower East Side (by tradition, near Bull’s Head Tavern).”

The evolution of New York City’s livestock infrastructure thus tells several stories: from the city’s slow spread northwards and the role of the railways and refrigeration in reshaping the urban relationship with agricultural production, to the adaptive reuse of food facilities as their original function becomes redundant.

In other words, from college bars to haute couture for sale in former packing houses, Manhattan still bears the imprint of beef.

IMAGE: Facing west on W. 34th Street at Twelfth Avenue, via Google Street View.

Meanwhile, the idea of an abandoned cattle tunnel buried under the unpromising intersection of Twelfth Avenue and Thirty-fourth Street, between the foundations of the Javits Convention Center and the West Side Railyards, is fascinating. Does it still exist? Did it ever? Or must it be filed, sadly, under the category of urban myth?

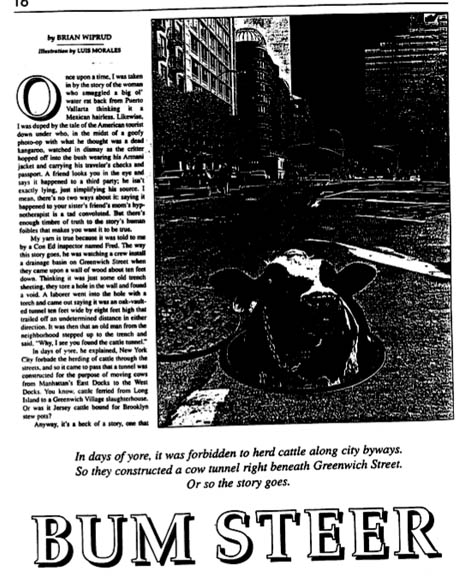

IMAGE: “Bum Steer,” by Brian Wiprud, available in full here.

The only reference to abandoned New York City cow tunnels on the internet leads to “Bum Steer,” a three-page article dated June 1997 from the Tribeca Trib, uploaded as a badly photocopied set of pdfs on the website of author Brian Wiprud. A crime novelist who supports himself by working as an underground utilities specialist at an engineering firm, Wiprud was similarly intrigued when he first heard about the cattle tunnel, although his introduction came from “a Con Ed inspector named Fred”:

The way this story goes, he was watching a crew install a drainage basin on Greenwich Street when they came upon a wall of wood about ten feet down. Thinking it was just some old trench sheeting, they tore a hole in the wall and found a void. A laborer went into the hole with a torch and came out saying it was an oak-vaulted tunnel ten feet wide by eight feet high that trailed off an undetermined distance in either direction. It was then that an old man from the neighborhood stepped up to the trench and said, “Why, I see you found the cattle tunnel.”

It turned out that practically everyone involved with New York City infrastructure had heard of the tunnel, but always at second-hand and accompanied by wildly varying locations and descriptions—made of steel, wood, or fieldstones, anywhere from Renwick Street to Gansevoort Street. By the end of the piece, Wiprud is forced to conclude (in his inimitable style): “Zero moo-moo tubes.”

![]()

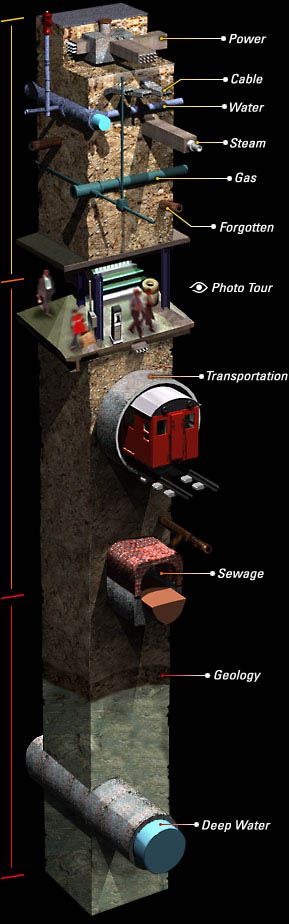

IMAGE: Subterranean New York City, as diagrammed by National Geographic (where a scale version and bibliography are also available).

Despite the lack of conclusive proof, the article points towards a couple of interesting ideas: the power of the imaginary cow tunnel and the architectural possibility of an ideal cow tunnel. First of all, the fact that the abandoned cattle tunnel is a pervasive myth surely says something significant about the urban relationship with food production and the return of the agricultural unconscious.

Secondly, in one of Wiprud’s more interesting diversions, he briefly wonders whether a cow tunnel is actually even a functional piece of architecture, considered from the point of view of cattle behaviour and livestock handling. According to his friend, Don Duncan the dairyman,

Problem is, cows aren’t so much skittish as they are clumsy, not to mention stump stupid. They might go into a dark tunnel, but the beasts are known to stumble and fall down on dry concrete if they blink too hard, for Pete’s sake. Now in a relatively dark, wet, slippery and relatively narrow tunnel, well, one cow might just fall and the others would trip right over each other in a pile-up. Happens in branding chutes. Real danger is that this tunnel sounds wide enough that there’d be a pile-up, some cows would panic, turn around, and make the herdsman into a doormat.

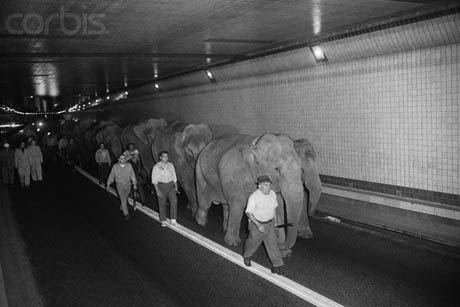

A subterranean cow tunnel, Wiprud speculates, is perhaps not even a valid building type—it’s the equivalent of a sheep sauna, or an elephant tightrope. (As an aside, and speaking of elephants, when the circus comes to town, they apparently prefer to walk through the Lincoln Tunnel, under the Hudson River, in order to get onto Manhattan island.)

IMAGE: Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey circus elephants walking through Lincoln Tunnel in May 1971, photo owned by Corbis.

However, according to Temple Grandin, the autistic savant who is also known as “the woman who thinks like a cow,” cattle can happily walk through a tunnel—but only if it’s designed correctly. The ideal cow tunnel, she explains in her book Animals in Translation, would use indirect lighting and a non-slip floor, as well as grey or beige paint, and sound-absorbent surfaces. Any sloping sections would be single file, the tunnel should get bigger along its length in the direction of movement, and finally—fabulously—it should be curved, so that the cattle “just sort of go round and round and round like the Guggenheim Museum.”

IMAGE: Temple Grandin-designed curved cattle chute in action, via You Tube.

With today’s resurgence of locavore-inspired backyard chicken coops and mobile, small-scale slaughterhouses, perhaps we will need a network of cow tunnels beneath New York City once again—connecting an organic, grass-fed future herd on Governor’s Island with the butchering facilities of Williamsburg, for example. In which case, Grandin’s blueprint offers an extraordinary vision of a inverse Guggenheim, spiralling its way in carpeted monochrome under the East River. Cow-designed infrastructure will finally join human artefacts—cables, freight tracks, nightsoil, and bunkers—buried beneath the city. Hundreds of years hence, a new sub-discipline of “companion species” archaeologists will stumble upon it, and use it to write histories of the animals whose co-evolution made us human…