As a curious coda to my previous post, in which Kew’s Plant Health and Quarantine Officer, Sara Redstone, notes the frequent mismatch between biological and political borders and discusses the role of quarantine in creating an artificial biological boundary, I was intrigued by this post on the Foreign Policy editors’ blog, Passport, reporting on political borders that have created biological effects.

The story starts with researchers at the University of Haifa, who partnered with Jordanian colleagues to study “a variety of reptile, mammal, beetle, spider and ant lion species on either side of the border in the Arava region.” According to the university’s press release, the team “set out to reveal whether the border – unknown to the species – could affect differences between them and their numbers on either side of the frontier, even though they share identical climate conditions.”

The question, in other words, is whether a border that exists only as a line drawn on a map, rather than an impassable physical boundary, can somehow become instantiated as biological fact?

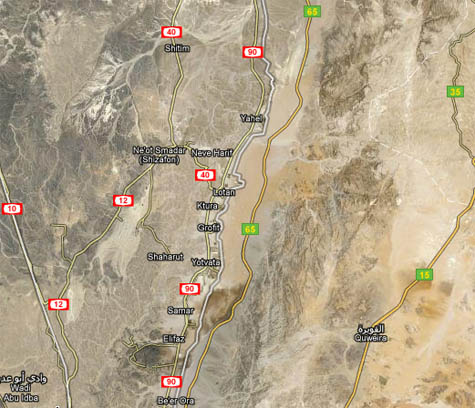

IMAGE: Satellite image of the Israel–Jordan border in the Arava desert, via Google Maps.

The research team, led by Dr. Uri Shanas, found substantive differences in the numbers, diversity, and even behaviours of animals on either side of the border:

The first study inspected the reptile population and revealed that the number of reptiles is similar on both sides, but the variety of species in the sandy areas of Jordan is significantly higher than the variety found in the sands of Israel. A second study revealed that Israeli gerbils are more cautious than their Jordanian friends, while a third study showed that the funnel-digging antlion population in Israel is unmistakably larger than in Jordan.

These differences were then analysed to find evidence of a hypothetical “border effect.” Dr. Shanas concluded that although the yard-high strand of barbed wire tracing the political demarcation “is not capable of keeping these species from crossing the border between Israel and Jordan,” it nonetheless “does stop humans from crossing it and thereby contains their different impact on nature.”

IMAGE: (left to right, top to bottom) Dorcas Gazelle via Wikimedia, Antlion via Trevor Jinks, Red Fox via Wikimedia, Gerbil via Wikimedia.

For example, the antlion surplus in Israel can be traced back to the fact that the Dorcas gazelle is a protected species there, while across the border in Jordan, it can legally be hunted. Jordanian antlions are thus disadvantaged, with fewer gazelles available to serve “as ‘environmental engineers’ of a sort” and to “break the earth’s dry surface,” enabling antlions to dig their funnels.

Meanwhile, the more industrial form of agriculture practised on the Israeli side has encouraged the growth of a red fox population, which makes local gerbils nervous; across the border, Jordan’s nomadic shepherding and traditional farming techniques mean that the red fox is far less common, “so that Jordanian gerbils can allow themselves to be more carefree.”

I’m fascinated by the fact that differing land-use practices, environmental legislation, and agricultural technology on either side of the political border have shaped two distinct and separate ecosystems of out what would otherwise be a shared desert environment.

Human activity has imprinted a virtual division onto the biological landscape, creating an immaterial, yet effective, behavioural border.