As a fun footnote to my last post: Last month, Popular Science offered an entirely speculative guide to eating dinosaur meat.

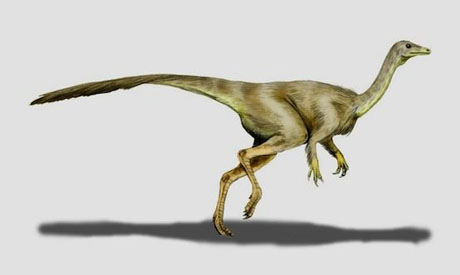

IMAGE: Struthiomimus altus, an ornithomimid from the Late Cretaceous, as illustrated by Nobu Tamura.

In consultation with David Varricchio, a professor of paleontology at Montana State University, journalist Erin Berger surveyed the megafauna of a pre-human epoch with the flavour preferences of a twenty-first century American consumer in mind. Her conclusion: An “ostrich-like dinosaur known as an ornithomimid would probably yield the most consumer-friendly cut of meat, while still maintaining a unique dinosaur taste.”

Extrapolating from the corn-fed beef that forms the majority of U.S. meat intake today, Berger and Varricchio assume that carnivorous or pescatarian dinosaurs would taste too gamey or fishy to meet with contemporary approval. After all, an animal’s diet plays the most significant role in determining its flavour profile as meat — not to mention its overall healthiness:

“When people ask me if a T-Rex would be good, well, I don’t think so,” David Varricchio […] says. “They’ve found jaw abnormalities that suggest they were eating fetid meat and had diseases that came about from prey items. They would be pretty parasite-laden.”

The type of activity that a dinosaur typically engaged in would also affect its flavour, with fast-twitch muscles resulting in white meat, and slow-twitch muscles, of the sort required for longer periods of steady motion, producing iron-rich red meat. Finally, the anatomy of the dinosaur would determine whether it would yield cuts of a satisfactory size and shape. Armoured tails “would probably be a lot of good white meat,” Varricchio tells Berger, while the long, muscular necks of tree-grazing sauropods would yield “a unique cut of sturdy red meat weighing several tons” that might well be considered a delicacy.

Ornithomimosaurs were large-thighed runners who, due to a lack of teeth, dined solely on plant matter. According to Varricchio, who has studied their bone histology, a steak from an ornithomimosaur’s hindquarters “would be a lean, slightly wild-tasting” cut.

Aside from the sheer pleasure of edible speculation, Berger’s piece is an enjoyable reminder that, on some level, the human perspective on the environment — even the pre- or non-human environment — is inevitably filtered through our biologically omnivorous, yet geographically, historically, and culturally adapted palate.