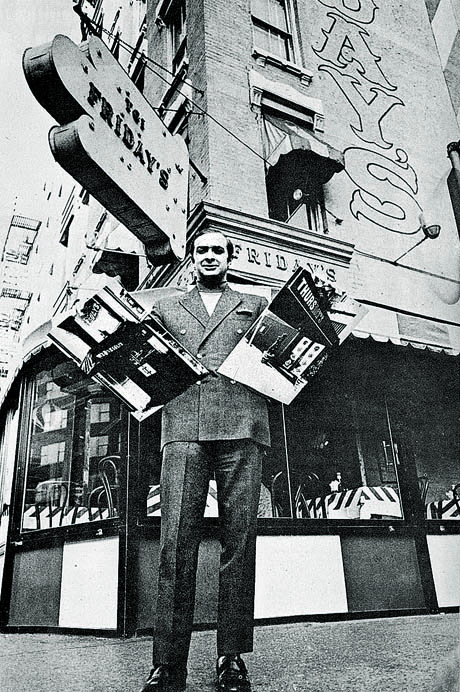

IMAGE: Alan Stillman in front of the first T.G.I. Friday’s location at 63rd Street & 1st Ave, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

In 1965, Alan Stillman was a young man living in Manhattan, who, in his own words, was “looking to meet girls.” The bar restaurant he founded, T.G.I. Friday’s, began life as a public cocktail party — the first neighbourhood joint to welcome both men and women alike, with the express motive to unite the two. Forty-five years later, Stillman’s singles’ bar in the Upper East Side has metamorphosed almost beyond recognition, spawning a landscape of casual dining franchises that redefined the American idea of the restaurant. Stillman himself went on to found iconic steakhouse, Smith & Wollensky, among several other restaurants.

Architect Krista Ninivaggi and I interviewed Stillman for the food issue of the New City Reader; below is an expanded version of the conversation we excerpted in print. In it, Stillman tell us how to create a cocktail party in public, what to do when you get a bad review in the New York Times, and what the restaurant, real estate, and movie businesses all have in common.

•••

New City Reader: What’s the story behind T.G.I. Friday’s?

Alan Stillman: I lived on 63rd Street between First and York. Easy access to the 59th Street bridge meant you could get out of New York quickly, so in that two or three block neighbourhood, there was a pile of airline stewardesses — and for whatever reason, there was also a whole bunch of models. Basically, a lot of single people all lived between 60th and 65th and between York Avenue and 3rd Avenue. It seemed to me that the best way to meet girls was to open up a bar.

NCR: Where were those people hanging out before you opened your bar?

Stillman: At the time, it was all cocktail parties. What would happen is that on Wednesday and Thursday, you’d start collecting information—things like, “On Friday night at 8 o’clock at 415 East 63rd Street, there’s going to be great party run by three airline stewardesses.” Then somebody else would say, “Well, I got a good one—it’s going to be run by one of the baseball players at his apartment.” You built up a cocktail list and you bounced from one place to the other. The cocktail parties were wild, by the way. But there was no public place for people between, say, twenty-three to thirty-seven years old, to meet.

IMAGE: P. J. Clarke’s today, via.

NCR: What about other bars — places like P. J. Clarke’s?

Stillman: P. J. Clarke’s was there — it had been in existence forever — but it wasn’t a meeting place. It was a guys’ beer-drinking hangout. There were very few women there. That was pretty typical of the New York bar scene at the time.

The other thing is that my timing was exquisite, because I opened T.G.I. Friday’s the exact year the pill was invented. I happened to hit the sexual revolution on on the head, and the result was that, without really intending it, I became the founder of the first singles bar.

The reason that it happened is that I used to stop into this corner bar near where I lived — a dirty old First Avenue bar with a bullet hole in the window called “The Good Tavern” — and I used to talk to the bartender. I would say to him, “You know, you ought to change the décor in here or do something with it — it would be a great place for all these people round here to meet each other. Eventually he said, “Why don’t you do it?” Five thousand dollars later, I had bought the premises with a short lease, and I was off and running.

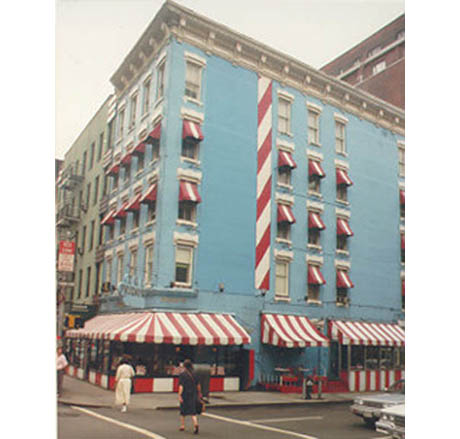

IMAGE: The original T.G.I. Friday’s location today, via T.G.I. Friday’s Facebook page.

NCR: Explain how you went about recreating that cocktail party atmosphere in a public space.

Stillman: All I really did was throw sawdust on the floor and hang up fake Tiffany lamps. I painted the building blue and I put the waiters in red and white striped soccer shirts. If you think that I knew what I was doing, you are dead wrong. I had no training in the restaurant business, or interior design, or architecture — I just have a feel for how to use all those things to create an experience.

I wanted T.G.I. Friday’s to feel like a neighbourhood, corner bar, where you could get a good hamburger, good french fries, and feel comfortable. At the time, it was a sophisticated hamburger and french fry place — apparently, I invented the idea of serving burgers on a toasted English muffin — but the principle involved was to make people feel that they were going to someone’s apartment for a cocktail party.

The food eventually played a larger role than I imagined it would, because a lot of the girls didn’t have enough money to stretch from one paycheque to the other, so I became the purveyor of free hamburgers at the end of the month.

I don’t think there was anything else like it at the time. Before T.G.I. Friday’s, four single twenty-five year-old girls were not going out on Friday nights, in public and with each other, to have a good time. They went to people’s apartments for cocktail parties or they might go to a real restaurant for a date or for somebody’s birthday, but they weren’t going out with each other to a bar for a casual dinner and drinks because there was no such place for them to go.

It took off extraordinarily quickly. In the first six to nine months, T.G.I. Friday’s got written up in Time, Newsweek, and the Saturday Evening Post. Then Maxwell’s Plum opened up across the street, which was another singles bar. It was really quite a phenomenon.

I believe that the first line in the history of bars, restaurants, and discos may have been at T.G.I. Friday’s. Inside of three months, we had to hire a doorman. One night I was tending bar, and he walked up to me and said, “Listen, there’s a dozen people standing outside, and we have no tables and no room at the bar. What do you want me to do?” And I said, “I tell you what. Why don’t you just tell them to wait, and when someone comes out, you’ll let them in.” He said that he didn’t know whether they would wait or not, and I said I didn’t know what else to tell him, and so he went back.

Next thing you know, I came out from behind the bar to get something and I looked outside and there were forty people standing in line. The next week we ended up buying velvet ropes. There was nothing like that anywhere else. You would either have a reservation at a fancy restaurant or you would just go into a bar or diner — nobody would wait in line for food and drink.

IMAGE: Alcoholic slushies at the T.G.I. Friday’s of today, via.

NCR: What else did you have to introduce or change in those early months?

Stillman: We had to change the way we ran the place completely. It was a long bar, with bar stools, and I don’t think anyone expected there to be people standing four deep behind the stools. Straightaway, we went from one bartender to three. The waiters couldn’t get through the aisles because of the crowds, so we had to adjust where the seating was. We had to change the menu to be able to get food out of the kitchen more quickly. It was a total readjustment, because no one expected to be doing the kind of business we were doing.

Inside of eighteen months, two more places opened up within a block. By the summer of 1965, the police had to come along, put up barriers, and close First Avenue between 63rd and 64th Street on Friday night from 8 p.m. until midnight, because there were so many kids going back and forth between these bars that the cars couldn’t get through.

We’d moved the cocktail party outside into the streets.

NCR: Did your strategy work? Did you meet good-looking girls?

Stillman: Have you seen the movie Cocktail? Tom Cruise played me! I was lucky enough to do it for three years — he only did it to make a movie. Even today, the advantage of being the guy behind the bar is huge. Why do girls want to date the bartender? To this day, I’m not sure that I get it.

IMAGE: Tom Cruise in Cocktail, via.

NCR: You opened up twelve T.G.I. Friday’s in total. How did you make the transformation from bar owner to businessman?

Alan Stillman: First of all, I’ll bet you Friday’s spawned thirty to forty restaurants and bars. We hired young people with bartending and waiting experience, and they made a lot of money, and a lot of them went out and opened up their own places.

But the second actual T.G.I. Friday’s was in Memphis, Tennessee. I didn’t pick it — they picked me. The original bar was two years old, and it had national recognition at that point. Somebody came in and said, “I’m from Memphis, Tennessee, and I own a shopping area down there with room for one of these. Will you sell me a franchise?”

I have to admit that I didn’t know what the word franchise meant. So I said, “If you have the money, I’ll be the partner and I’ll show you how to do it, and we’ll split it 50/50.” We shook hands and a year and a half later, we opened up a T.G.I. Friday’s in Memphis. People started coming in there from Little Rock and Nashville, and more guys walked in wanting to partner with me, and so I did the same thing again. Before I knew it I had five or six T.G.I. Friday’s round the country. It wasn’t pre-planned at all.

Then a couple of guys came in from Texas, and said, “We want to do this in Texas, and we want to do it at five times the size, on three floors, with a big central bar.” They had a lot of money and a lot of business expertise, and soon enough we were in Houston and Dallas and on it went.

IMAGE: Suburban T.G.I. Friday’s today, via.

NCR: Did changing the size of the restaurant change the atmosphere?

Stillman: The size didn’t change it as much as our expansion into the big southern suburban towns. Those cities have a very different way of interacting with the street in the first place, but the big shift was that during the day, we started to get families. We had very informal, casual food — you could get an omelette or a hamburger — so families were coming in with their kids. That was the big change. It took six or seven years, but T.G.I. Friday’s became a very different animal.

By 1971, the economy was very bad. At the time, we had a dozen Friday’s and we were trying to open up three more. By then, everyone was chasing us. There was Somebody Tuesday’s and Bennigan’s and this thing and that thing, and you needed big money to do it right and open three this year, and five next, and ten the year after that. I didn’t want to sell out, but I didn’t not want to either. While we were out trying to raise the money to expand, someone came to me and offered me enough money. With a million dollars at that time, you could retire and do nothing for the rest of your life. So I sold.

IMAGE: Interior of T.G.I. Friday’s today, via.

NCR: And moved on to Smith & Wollensky?

Stillman: I took a break first. I got married, we travelled around Europe, and that’s where I learned about food and wine. My wife and I spent a lot of time in France, and we became somewhat sophisticated. We saw a lot of French brasseries that served only French wine and French cuisine. When we came back here, the only thing like it was American steakhouses — but they didn’t serve any American wine. I thought that if I opened up a steakhouse and I served Californian wines, maybe I’d have something special and unique, and that’s how Smith & Wollensky got started. It was the American version of the French restaurants I loved in France.

I opened up Smith & Wollensky in 1977, with a list of forty-seven wines — half from California and half from France and Italy because we were scared to death that people weren’t going to order the American bottles, because they didn’t know what the hell they were. When you went into the nine other steakhouses in New York City at the time, you were asked if you wanted red or white.

There was nothing that was in itself hugely original — the menu was more extensive, the décor, the wines — but add it all together and when we opened, we were different from the other steakhouses in town. I did extensive steakhouse research, so we knew exactly what they were doing and what we wanted to do differently.

None of which helped, of course. The first review we got was the worst review in the history of the world. It was by Mimi Sheraton for the New York Times. We almost went broke. So we took out three full-page ads in the Times. At the time, the two big deal steakhouses in New York were The Palm and Christ Cella, and our ad showed two big matchbooks and said, “At last, a match for The Palm and Christ Cella!” We took it out three days in row, and business took off. We hadn’t done any advertising before. We didn’t know how to go out and pitch stories. At the time, no one advertised restaurants, especially not with full pages in the New York Times.

IMAGE: The original Smith & Wollensky in New York City, via.

NCR: What else was different about Smith & Wollensky, in terms of menu and decor?

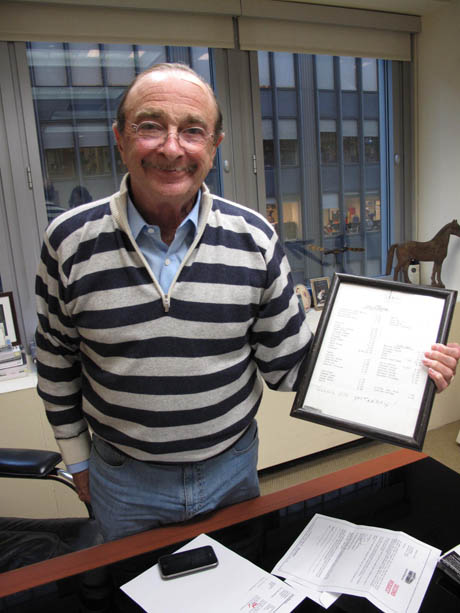

Stillman: I have the original menu here, but for the life of me, I can’t remember what we added that wasn’t on other steakhouse menus at the time.

We were in a former steakhouse that had been completely burnt down. We painted the exterior green and white, and we made the inside more — how shall I say this? — “elegant” than a typical steakhouse was at the time. It had more comfort to it — but that wasn’t because we intended it to be woman-friendly. It was a steakhouse, and at the time, steakhouses were male-oriented. Our target customer was people who ate at The Palm and Christ Cella — men my age. It’s only been in the past few years that I’ve seen people opening up “nightclub” steakhouses that are intended to attract single women. Now, if you want to see where a twenty-seven-year-old wants to eat steak in the year 2008, you should visit the restaurant my son Michael opened, Quality Meats.

IMAGE: Quality Meats, via.

A lot of people open up restaurants that fit their age level. It’s much easier for me to open up a restaurant that I understand and that my friends would go to, even today, than it is to open one up for thirty year-olds. I have no understanding of Michael’s new restaurant. I understand that it’s beautiful and the food is wonderful, but as to who it attracts and how — it’s completely foreign to me. It’s too loud and too dark for me and my friends.

I’ve been told that you find the same thing in books, movies, and theatre — that people create things that make sense for their age group.

NCR: Do you see any other analogies between creating a restaurant and directing a film or writing a book?

Stillman: It takes a similar level of creativity as being a movie director, other than you have be more of a businessman. When you walk into a restaurant, you’re looking for an afternoon or an evening of entertainment. The entertainment part of it — the atmosphere and the service and all the little touches — is as important as the food. You can serve the best food in the world, and if people didn’t like the atmosphere and the decor, they won’t come back.

You can’t get me to go to a restaurant that’s got terrible atmosphere and service—it doesn’t matter how good the food is. I won’t go. There’s an enormous amount of creativity in orchestrating a space and an experience so that it creates a particular feeling.

Look at this. [Points to wooden frame around the first Smith & Wollensky menu.] No one presented their menus in a frame at the time. There’s a tremendous amount of creativity in the restaurant business. The problem is that a tremendous number of people think that it requires nothing but creativity, but the business part doesn’t take care of itself.

IMAGE: Alan Stillman in his office with the original Smith & Wollensky menu. Photo by Krista Ninivaggi.

NCR: How did the feel of Smith & Wollensky evolve over time? What have you done to update it?

Stillman: This is something that I do think I’m good at. The New York City Smith & Wollensky is thirty-three years old, and there are others around the rest of the country that are ten or twelve years old. It’s about changing the place little by little, so that Smith & Wollensky is now fifty percent different than it was when it opened — but you wouldn’t know it. If you don’t know how to update your restaurant while keeping it the same, it will close after six or seven years.

The menu has to expand because you add new things to keep ahead of the competition but you have to keep the customer favorites. Dishware and glassware needs to be updated. It’s the things around the edges of the experience — sides, desserts, wines — that you can change. We’ve gone from four desserts to fourteen, made by an in-house pastry-chef.

I am very hands-on about this stuff. I choose the silverware, I make decisions about the decor, and I try every single thing on the menu. That’s my favourite part. The rest of it is just running a business. The fact that you’re selling steaks instead of widgets doesn’t make much difference.

IMAGE: Meat vault at Smith & Wollensky, via.

NCR: How did Smith & Wollensky grow? Did you plan to open more than one from the start?

Stillman: No, definitely not. I actually had partners at Smith & Wollensky that didn’t want to expand — they didn’t want to take the risk and they wanted to take money out of the business rather than put more in. That’s not a fault — it’s just a business decision that you make. Smith & Wollensky in New York City stayed on its own from 1977 to 1997. It took me twenty years to buy the right to expand from them.

NCR: Smith & Wollensky has remained in cities as it expands. Is that a conscious strategy?

Stillman: Smith & Wollensky is definitely an urban restaurant. These are big restaurants doing big dollars, and we have to be in big cities.

My second one was in South Beach, in Miami. We looked at Chicago, South Beach, Las Vegas, Philadelphia, Washington DC, and wherever the right property showed up first, we built.

IMAGE: Smith & Wollensky in Miami, via.

NCR: When you go looking for a Smith & Wollensky site, do you have a checklist?

Stillman: Yes. The bigger you get, the better your list gets. By the time you’re the size of McDonald’s, you don’t have to bother looking. You run your checklist up against some data and you know exactly where you can put your restaurant and where you can’t. Then it’s just a matter of getting hold of the real estate.

The single most important thing on Smith & Wollensky’s checklist is the ability to have an exterior look that is different from everybody else. That’s the deal-breaker — and the hardest part to find. We can’t put it in any old big office building because the owners won’t let us do that. We want people to drive by, not read the name, and say, “That’s Smith & Wollensky.” We started out like that with our first building, on the corner of Forty-ninth Street and Third Avenue, so it became our brand.

The other thing is that we build big restaurants. We’ve got seven hundred seats in most of our places, so we need the square footage. That’s an economic decision, not an atmosphere one. Big box, big tickets — that’s our formula.

The restaurant business does come down to real estate, though. A restaurant owner is renting or sub-letting you a piece of real estate for the evening, and how long you sit there and how much you spend determines whether they’re going to be successful or not.

Once I was in the $75 ticket business, then I started looking around and getting other ideas. I like to fill holes — figure out what’s missing and supply it. I opened Park Avenue and The Post House and the Manhattan Ocean Club, which has since turned into Quality Meats.

NCR: What’s missing in the New York City restaurant-scape right now?

Stillman: There’s very little missing in New York at the moment. It’s the food capital of the world, in my opinion. There is still room for originality — for example, my son, Michael, opened up the only Polynesian restaurant in town. There are not many holes like that to be filled, but there are other kinds of holes — the kind that you can fill with décor, atmosphere, prices, and imagination. And there are geographical holes — for example, I personally think that in Midtown, there is room for a high-end Indian restaurant.

Of course, you don’t have to open up something that fills a hole. There are a lot of people doing perfectly good business opening up more same-old steakhouses. That’s just not where the fun is for me.

NCR: Are there any current food trends that you find particularly intriguing?

Stillman: I don’t quite get the celebrity chef thing. What are these guys doing cooking meals on television? And why do they have multiple restaurants? Star chefs used to have a restaurant, and when you went there, he cooked for you. To me, if you’re not in the kitchen cooking, then I’m not eating your food.

I’m not condemning Wolfgang Puck and the others, but this celebrity chef trend has changed the feeling of what cooking is at a certain level.

Now Steve Wynn, with his hotels in Las Vegas, put his foot down and made star chefs sign multi-year contracts that they would be there five nights a week. Mr. Wynn has got 1500 rooms and a gambling empire on top of the restaurants, so he can afford to go to Paul Bartolotta and pay him a million dollars a year to be there five nights a week. And the result is probably the best Italian seafood restaurant in the whole world.

NCR: Do you prefer eating out at restaurants or eating at home?

Stillman: By choice, I would eat out six nights a week. It’s better and easier — and even if you were wealthy enough to have a personal chef who did all the work for you, it seems to me as though it would get boring after a while. I want to go out and see what’s going on in the city, and try different cuisines, and different cooking styles. The only reason I’d want to stay home once in a while is that maybe I want to watch a movie or read a book over dinner.

I eat in one of my own restaurants once a week. The rest is split: two-thirds, places I know and love; and one-third, new places I want to try. In my head, I’m not going for business reasons, but my wife will tell you that when I’m out, whether I know the place or not, if she allowed me I’d pull out a pen and paper and start taking notes. She’s probably right. I’m a great stealer. I see things and bring them back to the business all the time.

[NOTE: I owe an enormous thanks to Alan Stillman for sharing his time and reminiscences so generously, and to Krista Ninivaggi, who coordinated and co-conducted the interview.]